Beyond Muscle Tension: How Chronic Neck Pain Rewires Motor Control

1. Introduction: The Invisible Armor of Neck Pain

We have all experienced it: that sudden, reflexive "guarding" that occurs when the neck feels vulnerable. It manifests as a persistent stiffness—a sense that your muscles are locked in a defensive crouch. Traditionally, patients and clinicians alike have viewed this as simple muscle tension or a mechanical restriction to be rubbed out or stretched away. However, at Chicago Spine and Sports, we view this sensation through a more sophisticated lens: "motor control." This is the complex, high-speed dialogue between your brain and your muscles to protect the spine.

Understanding why the body creates this invisible armor is essential for moving beyond temporary relief toward genuine recovery. This post distills groundbreaking research by Meisingset et al. (2015), which reveals how chronic neck pain fundamentally rewires the way we move. These findings revolutionize our clinical approach: a stiff neck is often not a muscle in need of stretching, but a strategic motor pattern in need of retraining.

2. The General Stiffening Strategy: When Protection Becomes a Prison

Stiffness is rarely just a symptom; in the context of chronic pain, it is a deliberate, albeit counterproductive, strategy the nervous system employs to "stabilize" the cervical spine. By initiating reflexive protective guarding, the brain attempts to minimize any movement it perceives as a threat.

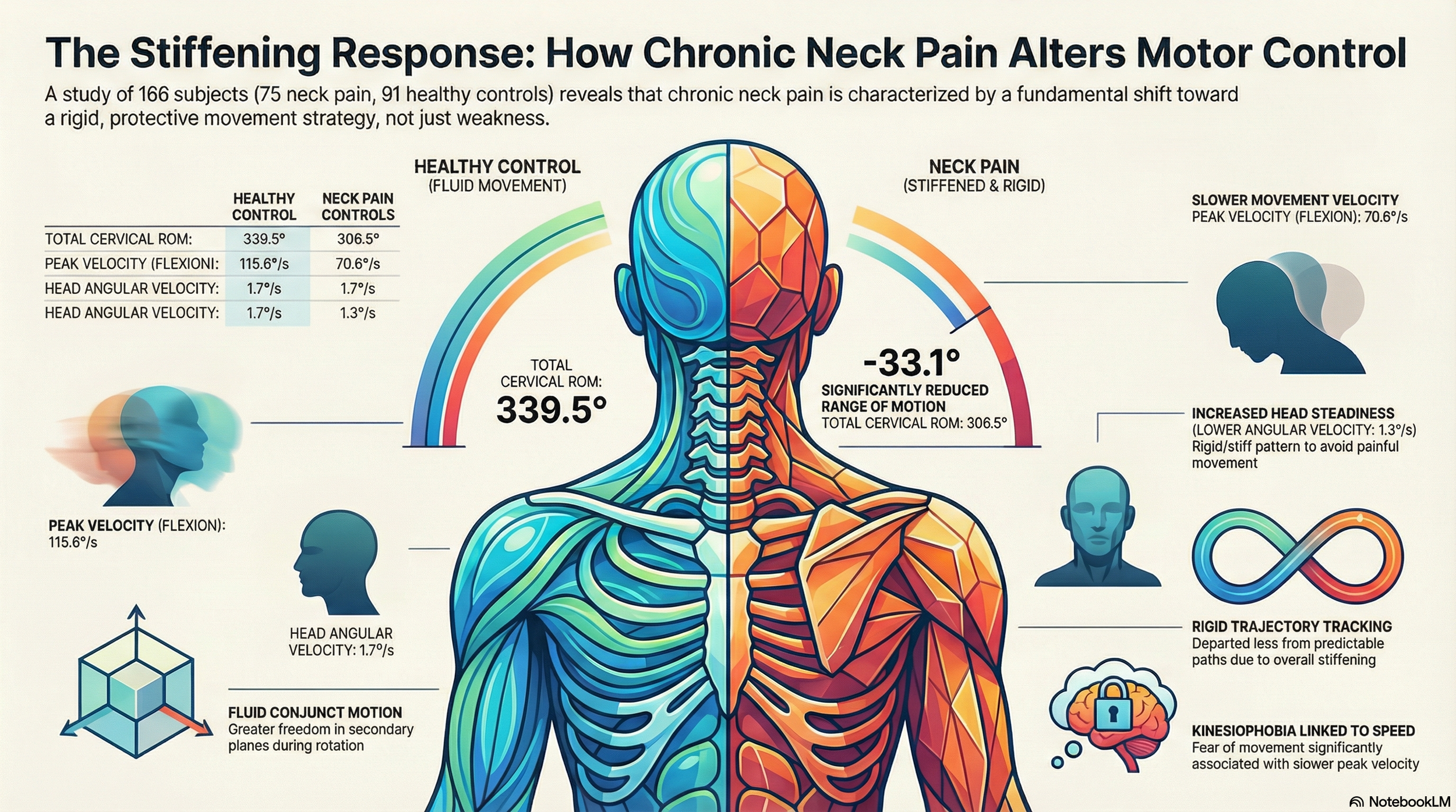

A Rigid Motor Control Pattern Meisingset et al. (2015) evaluated 166 subjects and found that patients with Neck Pain (NP) demonstrated a significantly "stiffer and more rigid neck motor control pattern" compared to healthy controls. This change in the quality of movement is a hallmark of the chronic pain state.

The "So What?": Loss of Freedom This rigidity manifests most clearly in the reduction of "conjunct motion"—the neck’s natural ability to move smoothly across multiple planes simultaneously (such as rotating while slightly flexing). When the neck loses this "freedom of motion," it becomes mechanically inefficient. This creates a cycle where the more rigid the neck becomes, the more the mechanical load is concentrated on specific segments, leading to further pain and reinforcing the "bracing" response.

"NP patients showed an overall stiffer and more rigid neck motor control pattern compared to HC, indicated by lower neck flexibility, slower movement velocity, increased head steadiness and more rigid trajectory head motion patterns." — Meisingset et al. (2015)

3. The Speed Limit of Fear: How Kinesiophobia Dictates Performance

The intersection of psychology and biomechanics is a critical frontier in spinal health. When we are in pain, we don't just move less; we move with a self-imposed "speed limit."

The Flexion-Extension Governor The research highlighted a compelling link between "peak velocity" (the maximum speed of a neck movement) and "kinesiophobia"—the fear of physical movement resulting from a feeling of vulnerability. Interestingly, this association was most significant during flexion and extension (nodding movements) rather than rotation.

The "So What?": The Mental Governor Slower movement in these patients wasn't merely a physical limitation caused by tissue damage. Instead, peak velocity was the only variable significantly associated with the fear of being injured. Essentially, the patient’s mental state sets a "governor" on physical performance. In our clinic, we see this as the brain trying to stay within a perceived "safe" zone, even when the tissues have long since healed.

Movement Metric

Healthy Controls (HC)

Neck Pain (NP) Trends

Peak Velocity (Flexion/Ext)

Higher (~115.6 °/s)

Significantly Lower (~70.6 °/s)

Peak Velocity (Rotation)

Higher (~158.9 °/s)

Lower (~109.3 °/s)

Peak Velocity (Lateral)

Higher (~85.7 °/s)

Lower (~57.9 °/s)

4. The Paradox of "Perfect" Head Steadiness

In athletics, steadiness is a virtue. In spinal mechanics, however, "over-steadiness" is often a red flag for dysfunction.

The Isometric Stiffening Response During tests designed to measure head steadiness, NP patients exhibited lower angular velocity than healthy subjects. In simpler terms, they were "steadier" than the healthy participants.

The "So What?": The Metabolic Cost of Bracing This "perfect" steadiness is achieved through the co-contraction of agonist and antagonist muscles—essentially, the patient is "pressing the gas and the brake" at the same time to prevent any movement. While this makes the head appear steady, it is incredibly metabolically expensive. This internal bracing explains the "fatigue-pain cycle" we often see clinically. It is why a patient’s neck may feel significantly worse by 4:00 PM; they aren't just tired from the day—they are exhausted from the constant, invisible work of bracing their spine.

5. Precision Through Rigidity: The Trajectory Insight

Healthy movement is naturally "noisy" and variable. Our bodies possess various "Degrees of Freedom," allowing us to distribute mechanical loads across different tissues each time we move.

Predictability vs. Unpredictability The research used two tests: the "Figure of Eight" (predictable) and the "Fly Test" (unpredictable). In the predictable test, NP patients surprisingly departed less from the pattern than healthy controls. They used their stiffening strategy to gain a precision advantage. However, when the "fly" moved randomly, this strategy failed. Without a predictable path, the rigid neck could no longer maintain its accuracy.

The "So What?": Reclaiming Variability By being "more accurate" through rigid control, NP patients lose the movement variability required to protect the spine long-term. Recovery at Chicago Spine and Sports focuses on moving from this "protective rigidity" back to "freedom of motion," allowing the spine to once again distribute loads across its entire structure rather than hammering the same spot repeatedly.

6. The Balance Threshold: Exposing Dysfunction Under Stress

The neck is a primary sensory organ for balance, serving as the bridge between your eyes and your inner ear.

Postural Sway and the Balance Pad In stable environments, the "stiffening strategy" is effective enough to mask underlying balance deficits. NP patients only showed significantly higher postural sway when placed on an unstable "balance pad." Furthermore, there was a trend of less sway during the dynamic "Figure of Eight" standing test—a phenomenon known as "dual-task stiffening."

The "So What?": Masking the Deficit When the environment becomes unpredictable, the stiffening strategy is exposed as a failure. This explains why a patient may feel stable walking on a flat floor but feel vulnerable or "off-balance" when navigating a crowded room or uneven sidewalk. The rigid control that protects them in the clinic fails them in the real world.

7. Conclusion: Beyond the Brace – A New Path to Recovery

The "Proprioception Surprise" of the Meisingset study is perhaps its most vital takeaway: Joint Position Error (the sense of where the head is) was largely normal in neck pain patients. This tells us that "the map is fine; the driver is just being too cautious." The problem isn't a lack of sensory input, but a chronic choice by the brain to employ a "stiffening strategy."

Reclaiming Smoothness Recovery is not just about strength; it is about unlearning rigidity. If your recovery plan only focuses on "stabilizing" an already braced neck, it may be reinforcing the problem. True healing involves reclaiming smoothness, reducing the metabolic cost of co-contraction, and restoring the degrees of freedom your spine was designed to enjoy.

As you move through your day, ask yourself: Are you moving with genuine freedom, or are you living inside a protective, rigid armor of your own making?

A Chicago Spine and Sports Insight.